A History of the Earliest Milams in Virginia

Long before our Revolutionary War, British Milam(s) made their way to Virginia. John Mylam of Bristol was Shipmaster of the sailing vessel John and made three voyages to the Virginia Port of York in 1699, 1700 and 1701. [1, 2] The Royal Navy Shipping Lists for York describe the John as a square stern ship of 60 tons. Its arrival cargo were “European goods” and departing cargo, as always, was tobacco.

It may have been his death in Virginia which was administered in the Church of England's Prerogative Court of Canterbury, London in December 1701. American Wills and Administrations in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 1610 – 1857 states in part:

"Milam, John, of Bristol, who died in Virginia. Administration to Dorothy, wife of Richard Dyer, aunt and guardian of the children, John and Elizabeth Milam". [3]

In 1711, a passenger, John Mylam, sailed from Bristol to Virginia on the galley Cranfield. [5] There are no records for its arrival in Virginia since the Shipping Lists from 1708 through 1724 are missing. Thus I was not able to learn which Virginia port the Cranfield entered. It is not known if this John Mylam was a merchant or settled in the colony. But abstracts of court records for the counties of eastern Virginia have no record for this John Mylam so it appears he didn't settle there.

More interesting for us were the Milams from the port of Whitehaven, England, because over three generations they made many voyages to Virginia as shipmasters and merchants. In Whitehaven they purchased a variety of textiles, tools and leather goods like gloves, shoes, horse saddles and bridles and sold these items in Virginia to raise capital. Then over the course of the Summer they contracted to purchase tobacco for their Fall return voyage making a handsome profit on both ends. [732] Over time Whitehaven became a major port for the colonial tobacco trade - by 1745 second only to London - and for the export of indentured servants (link) to Virginia [712].

I can easily imagine that John and Thomas Milam, the patriarchs of the Virginia Milam(s), were among these transported servants as you will learn by reading the details of my research here (link).

The Earliest Milam Settlers in Virginia

Leaving the origin of the Milams aside, by the early 1760s court records document Milams in these counties in the Colony and Dominion of Virginia ( date is for their first court record ):

| Thomas Milam (24 MAR 1738) in Orange (Culpeper) County [9, 10] |

| John Milam (27 MAR 1760) in Orange (Culpeper) County [309] |

| William Milam (26 MAY 1760) in Bedford County [6] |

| Benajmin Millam (26 AUG 1760) in Orange (Culpeper) County [446] |

| John Milam Sr. (DEC 1750) in Brunswick County [7, 636] |

| Edward Milam (24 JAN 1754) in Brunswick County [8] |

| Adam Milam (27 NOV 1760) in Brunswick County [637] |

| Samuel Milam (6 MAR 1761) in Chesterfield County [638] |

| James Milam (7 MAY 1762) in Chesterfield County [639] |

| Edmund Milam (2 OCT 1770) in Brunswick County [703] |

Based upon his hand writing we now know that the John Milam Sr first found in Brunswick County (1750) then in Chesterfield County (1760) then later in Halifax County (1764) and finally in York County, SC (~1787) is the same man, the same John Milam. You may read about this important discovery here (link) .

Having read thousands of pages of county court records for these men, the evidence is overwhelming that the Milams arrived in Virginia as indentured servants (link), as did 75% of Virginia immigrants. They indentured themselves as servants to pay for their Atlantic passage from Great Britain. Since such servants were not paid a wage during their 4 - 7 years of indenture, they had to borrow money afterwards to get started. From time to time these former servants typically fell behind in the payment of money they owed for their land lease or to merchants. Like most everyone, the Virginia Milams were sued in their county courts for these debts as you may read in the Court Records for each man by clicking on his name: Thomas (link) and John Milam Sr (link).

Thus it was difficult for them to save enough money to buy land of their own. For example, it took Thomas 12 years from when he first appeared in Orange County records for "a debt due by bill" on 24 March 1738 until he received his first land grant in January 1750. It was a similar story for John Sr whose first court appearance in the Brunswick County court was for a "case of debt" on 25 JUN 1754 and his first purchase of 100 acres of land was in April 1764 - some 10 years later. John Sr and Thomas worked long and hard after their servitude to acquire their first farm where they then had to erect a shelter, clear the forested land and plant crops. For details about the shelters these early Virginia settlers constructed, please read my chapter on Pioneer's Houses here (link).

|

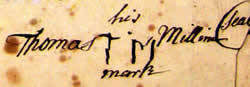

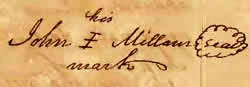

Another important point about our patriarchs, the first generation Milams — Thomas of Orange / Culpeper counties and John Sr of Brunswick / Chesterfield counties — signed deeds, contracts and wills with his mark rather than their signature because they lacked the literacy skills to write their name. In those situations - typical of most of the population - the attorney who wrote the document would write their name and leave a space in the middle of it for his mark as you can see:

NOTE: I think the reason Thomas Milam learned to write his initials and his sons became literate was because his wife, Mary Rush, was a Quaker from a wealthy and literate family. Details are here (link). Witness their son Moses Milam's Memorandum here (link). And it's why sons John and Rush could be appointed Constables and John and William Lieutenants in the Bedford County Militia since literacy was required.

This is how award winning author, David Hackett Fischer, described the immigrants to Virginia in his 2000 best selling history, Bound Away:

"New England had drawn its population mostly from the middle of English society. Virginians came in greater numbers from both higher and lower ranks. In quantitive terms {Governor Sir William} Berkley's "distressed cavaliers" (link) were only a small part of English migration to the Chesapeake colonies. The great mass of Virginia's immigrants were humble people of low rank. More than 75% of the immigrants came as indentured servants....Two-thirds of Virginia's colonists were unskilled laborers, or farmers in the English sense - agraian tenants who worked the land of others. Only about 30 percent were artisans. Most were unable to read or write...." [15]

|

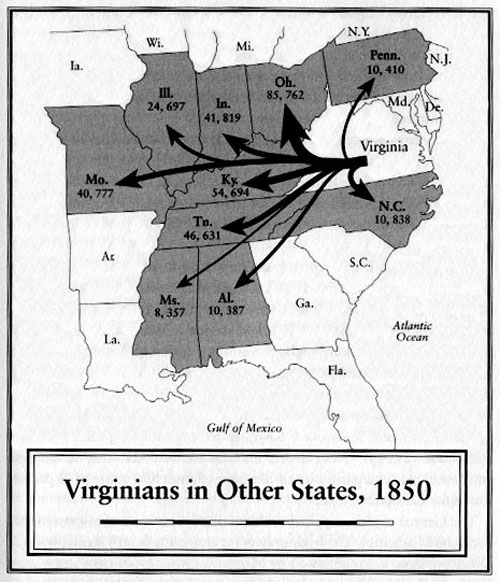

The essential societal difference between the settling of New England and the settling of the Mid-Atlantic Colonies were the demands of the Tobacco Economy (link) which was the foundation of the latter. Indeed tobacco was so important that it literally became the common currency (link) after 1642. Because tobacco farming was so labor intensive, it required the importation of not only indentured servants but, increasingly, African slaves, the King's prisoners from the Jacobite uprisings in Ireland (1690) and later Scotland (1715 & 1745) and even London City's convicts. [641, 642, 705] This is why many second generation Milams removed from Virginia: it was simply unprofitable for family farmers to compete against slave labor. [478, 479] They were not the only ones to leave. The map below, based on a question in the 1850 United States Census, illustrates the size of the exodus from the State of Virginia; details here (link) . As you can see, many fled to the slave free Northwest Territory (OH, IN, IL).

|

There was no disgrace in the life of the immigrant indentured servant (link) after all three quarters of their neighbors had been servants. These were simply the facts for the vast majority who couldn't otherwise afford their passage to America. [640] Indeed two United States Presidents had been indentured servants: Andrew Johnson to a tailor and Millard Fillmore to a clothmaker. The facts of these Milams' existence - as documented in the county Court Records webpage for each man - are a testament to just how much our hard working ancestors endured to succeed in this new land.

I am a descendent of Thomas Milam (of Orange / Culpeper Counties) youngest son, Rush, who was mentioned in Thomas' Will (image). [126] For that reason I initially researched the lives of Thomas and his sons in the court records of Orange County; their portion was named Culpeper County in 1749.

My research of Thomas's life led me to search for the exact location of Thomas' property in these counties and to discover his wife, Mary Rush, and her father, William Rush IV, an Orange County Constable (link) who farmed just to the southeast of Thomas Milam. You may view his land plat on a current map by clicking here (link). Although the ancestors of Thomas Milam are still unknown, William Rush IV's lineage [11] can be traced to his great grandfather, William Rush I, who immigrated to Virginia between 1635 and 1650. [12, 13] His portion of Northumberland County was partitioned off as Westmoreland County in 1653 where there are many records for the four generations of William Rush(s). My history of the Rush family of Westmoreland County may be found under the Mary Rush Family tab or by clicking here (link)

After Thomas removed to Bedford County in 1761, I researched the court records there. All together I have read the court records for the counties where Thomas and his sons lived from 1730 through 1793.

{ Incidentally, Oliver Milam of www.milam.com (link) recently found that the Boston merchant John Milam removed to Ireland with his family and sons in 1652. Thus they couldn't have settled in Virginia as some had imagined. }

How were Thomas Milam and John Milam Sr of Colonial Virginia related?

It was long believed that Thomas Milam and John Milam Sr were brothers because of their similar age and their eventual location in the Piedmont of Virginia. However, it was curious that initially they settled in counties some 160 miles apart according to court records.

It turns out that the descendants of these early Virginia Milams are very closely related. What we learned in 2017 from the Family Tree DNA Milam Surname Project is that most Milams in the United States (40 of 41 tested) are the same genetic Haplogroup:

and are descended from the Colonial Virginia Milams.

By 2021, the results of FTDNA BIG Y DNA sequencing analyses of fifteen members of our Project proved they were not brothers. You may read the details here (link) .

The one Project member who is not genetically related is a descendant of a William Mileham, born circa 1756 in the Colony of Pennsylvania. He has a very different Haplogroup: I1-M253>F2642. There may well be other Milams in America of different genetic families since we have found at least six genetically distinct Milam / Mileham / Milum families in Great Britain. You may read my discussion of Milam Genetic Genealogy by clicking here (link) and read about our Y-DNA testing of 26 British Milams here (link) .

Photos at the top of this page show in the distance the north side of Doubletop Mountain where Thomas Mylam had 203 acres along the "south fork of the Robinson River", present day Rose River. The photo was taken from the Skyline Drive ~ 5 miles north of Milam's Gap in the Shenandoah National Park just north of Big Meadows looking southeast. The summit of Doubletop is just right of center.

If you hover your mouse over it, a second photo appears which was taken from the summit of Old Rag Mountain looking south to Doubletop. Thomas Mylam's property is in the center of view. On the far left, East, where Doubletop descends to join the Robinson River valley lies the land of the Rush brothers, William and Benjamin. The summit of Doubletop is at the far right, West. In the foreground running the width of the photo is the south slope of Old Rag. Full credit to Robert Vernon (link) for locating Thomas Milam's land for me.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NOTE TO READERS: All the words in bold type face are links to photographs, maps or word definitions in the Glossary. I urge you to explore by left clicking on them. Once you have clicked a link, it will be displayed in dark red type. Some of the images have "roll–overs" whereby, if you hover your cursor over the image, a second image appears - as above. In the case of historical documents, the second image will be a typed transcription of the colonial script as demonstrated here (link) . Citations are enclosed within brackets [ ] and are found on the Citation link under Resources. Clarifications within my writing will be found within ( ) and within direct quotes will be found within { }. Since the spelling of the "Milam" name often varies even within a single document, I will sometimes revert to the generic "Milam" rather than using the various spellings.

Try clicking on "Will" (link) in the text above and this word: Hogshead (link) - be sure to click "Image" at the end of this definition too.